Sneak peek at the amazing winner photos in Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Presse contact

Bent Bøkman

Press Officer

Natural History Museum Denmark

University of Copenhagen

Phone: (+45) 53 83 30 41

Mail: bent.boekman@snm.ku.dk

Guidelines for use of photos

Photos on this page may only be used in connection with press coverage of the exhibition Wildlife Photographer of the Year (WPY57) at the Natural History Museum of Denmark.

The images are available for download in a web-friendly resolution for digital use only. Please click each image to download.

For high-resolution images for print, please contact our press officer Bent Bøkman.

All requests for front cover use must be sent to wildpress@nhm.ac.uk.

A maximum of 12 images are available per media outlet.

Images should not be cropped or altered. Sensitive cropping is permitted with permission from the photographer.

PHOTO CREDIT IS REQUIRED. The credit information can be found in the image descriptions: [Photographer's name] / Wildlife Photographer of the Year.

Copyright must be clearly attributed to the photographer.

PLEASE READ terms and conditions for use of press photos.

Winner of Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Shane Gross (Canada) looks under the surface layer of lily pads as a mass of western toad tadpoles swim past.

Adult grand title winner

Shane snorkelled in the lake for several hours, through carpets of lily pads. This prevented any disturbance of the fine layers of silt and algae covering the lake bottom, which would have reduced visibility.

Western toad tadpoles swim up from the safer depths of the lake, dodging predators and trying to reach the shallows, where they can feed. The tadpoles start becoming toads between four and 12 weeks after hatching. An estimated 99% will not survive to adulthood.

Young Wildlife Photographer of the Year

Alexis Tinker-Tsavalas (Germany) rolls a log over to see the fruiting bodies of slime mould and a tiny springtail.

Young Grand Title Winner

Alexis worked fast to take this photograph, as springtails can jump many times their body length in a split second. He used a technique called focus stacking, where 36 images, each with a different area in focus, are combined.

Springtails are barely two millimetres long (less than a tenth of an inch). They are found alongside slime moulds and leaf litter all over the world. They feed on microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi, improving soil by helping organic matter to decompose.

Category winners

Alberto Román Gómez (Spain) contrasts a delicate stonechat bird with a hefty chain.

Watching from the window of his father’s car at the edge of the Sierra de Grazalema Natural Park, Alberto found this young bird tricky to photograph as it was quickly flying back and forth, gathering insects. To Alberto, the stonechat displayed a sense of ownership, as if it were a young guardian overseeing its territory.

This young bird has not yet developed its adult call, which sounds like two stones tapped together. Stonechats tend to prefer open habitats and typically perch on fences.

Parham Pourahmad (USA) watches as the last rays of the setting sun illuminate a young Cooper’s hawk eating a squirrel.

Over a single summer, Parham visited Ed R Levin County Park most weekends to take photographs. He wanted to showcase the variety of wildlife living within a busy metropolitan city, and to illustrate that ‘nature will always be wild and unpredictable’.

The Cooper’s hawk is a common species across southern Canada, the USA, and central Mexico, where it inhabits mature and open woodlands. These adaptable birds also live in urban spaces, where there are tall trees to nest in, and bird feeders that attract smaller birds, which they can prey on.

Igor Metelskiy (Russia) shows a lynx stretching in the early evening sunshine, its body mirroring the undulating wilderness.

The remote location and changing weather conditions made access to this spot – and transporting equipment there – a challenge. Igor positioned his camera trap near the footprints of potential prey.

It took more than six months of waiting to achieve this relaxed image of the elusive lynx. A survey carried out in 2013 estimated the entire Russian lynx population was around 22,500 individuals, with numbers for the Russian Far East, including those in Primorsky Krai, at 5,890.

John E Marriott (Canada) frames a lynx resting, with its fully grown young sheltering from the cold wind behind it.

John had been tracking this family group for almost a week, wearing snowshoes and carrying light camera gear to make his way through snowy forests. When fresh tracks led him to the group, he kept his distance to make sure he didn’t disturb them.

Lynx numbers usually reflect the natural population fluctuations of their main prey species, the snowshoe hare. With climate change reducing snow coverage, giving other predators more opportunities to hunt the hares, hare populations may decline, in turn affecting the lynx population.

Jack Zhi (USA) enjoys watching a young falcon practising its hunting skills on a butterfly, above its sea-cliff nest.

Jack has been visiting this area for the past eight years, observing the constant presence of one of the birds and photographing the chicks. On this day it was a challenge to track the action because the birds were so fast.

Should this young peregrine falcon make it to adulthood, tests have shown it will be capable of stooping, or dropping down on its prey from above, at speeds of more than 300 kilometres per hour (186 miles per hour).

Hikkaduwa Liyanage Prasantha Vinod (Sri Lanka) finds this serene scene of a young toque macaque sleeping in an adult’s arms.

Resting in a quiet place after a morning of photographing birds and leopards, Vinod soon realised he wasn’t alone. A troop of toque macaques was moving through the trees above. Vinod spotted this young monkey sleeping between feeds and used a telephoto lens to frame the peaceful moment.

Toque macaques easily adapt to human foods, and the encroachment of plantations into their habitat has seen an increase in incidents of shooting, snaring and poisoning by farmers trying to preserve their crops.

Karine Aigner (USA) recognises the skin of a yellow anaconda as it coils itself around the snout of a yacaré caiman.

The tour group Karine was leading had stopped to photograph some marsh deer when she noticed an odd shape floating in the water. Through binoculars, Karine quickly recognised the reptiles and watched as they struggled with each other.

Caimans are generalist feeders and will eat snakes. As anacondas get larger, they will include reptiles in their diet. It’s hard to determine who is the aggressor here. On the snake’s back are two tabanids, blood-sucking horseflies that are known to target reptiles.

Ingo Arndt (Germany) documents the efficient dismemberment of a blue ground beetle by red wood ants.

‘Full of ant’ is how Ingo described himself after lying next to the ants’ nest for just a few minutes. Ingo watched as the red wood ants carved an already dead beetle into pieces small enough to fit through the entrance to their nest.

Much of the red wood ants’ nourishment comes from honeydew secreted by aphids, but they also need protein. They are capable of killing insects and other invertebrates much larger than themselves through sheer strength in numbers.

Justin Gilligan (Australia) creates a mosaic from the 403 pieces of plastic found inside the digestive tract of a dead flesh-footed shearwater.

Justin has been documenting Adrift Lab’s work for several years, often joining them on beach walks at dawn to collect dead chicks. The team brings together biologists from around the world to study the impact of plastic pollution on marine ecosystems.

Studies found that three quarters of adult flesh-footed shearwaters breeding on Lord Howe Island – and 100% of fledglings – contained plastic. The team, including a scientist from London’s Natural History Museum, discovered it causes scarring to the lining of the digestive tract, a condition called plasticosis.

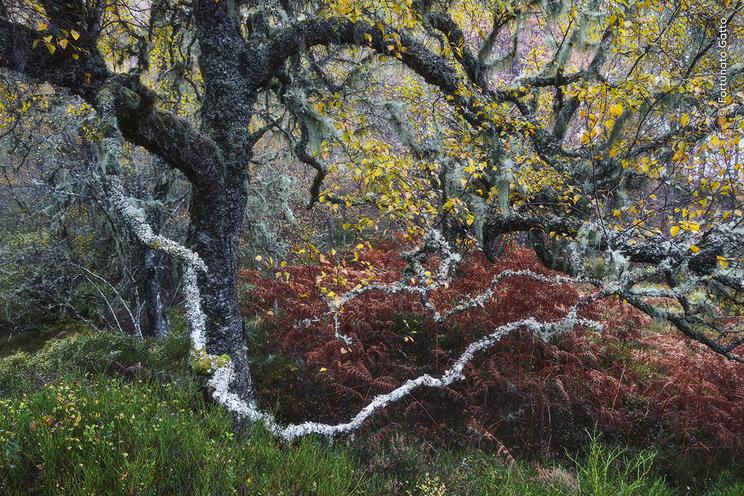

Fortunato Gatto (Italy) comes across a gnarled old birch tree adorned with pale ‘old man’s beard’ lichens.

Fortunato often visits the Glen Affric ancient pinewoods alone to lose himself in its intricate, chaotic, timeless beauty. The pale ‘old man’s beard’ lichens indicate that it’s an area of minimal air pollution.

Glen Affric is home to the highest concentration of native trees in the UK, making it a vital ecosystem. Analysis of pollen preserved in the layered sediments shows that the forest has stood here for at least 8,300 years.

Jiří Hřebíček (Czech Republic) creates an impressionistic vision of this perching carrion crow.

Jiří often visits his local park in Basel as it’s an ideal place to experiment with camera techniques. To create this painterly effect of a sitting carrion crow, Jiří deliberately moved his camera in different directions while using a long shutter speed.

Carrion crows are intelligent birds that have successfully adapted to living alongside humans, with gardens and parks providing a regular food supply. In Switzerland they are found north of the Alps, with some of the highest concentrations around Basel.

Matthew Smith (UK/Australia) carefully photographs a curious leopard seal beneath the Antarctic ice.

Matthew used a specially made extension he designed for the front of his underwater housing to get this split image. It was his first encounter with a leopard seal. The young seal made several close, curious passes. ‘When it looked straight into the lens barrel, I knew I had something good.’

Though leopard seals are widespread and abundant, overfishing, retreating sea ice and warming waters mean that krill and penguins – their main food sources – are both in decline.

Robin Darius Conz (Germany) watches a tiger on a hillside against the backdrop of a town where forests once grew.

Robin was following this tiger as part of a documentary team filming the wildlife of the Western Ghats. On this day, he used a drone to watch the tiger explore its territory before it settled in this spot.

The protected areas in the Western Ghats, where tigers are carefully monitored, are some of the most biodiverse landscapes in India and have a stable population of tigers. Outside these areas, where development has created conflict between humans and wildlife, tiger occupancy has declined.

Britta Jaschinski (Germany/UK) looks on as a crime scene investigator from London’s Metropolitan Police dusts for prints on a confiscated tusk.

Britta spent time at the CITES Border Force department where confiscated animal products are tested. Newly developed magnetic powder allows experts to obtain fingerprints from ivory up to 28 days after it was touched, increasing the chances of identifying those involved in its illegal trade.

The International Fund for Animal Welfare has distributed more than 200 specially created kits to border forces from 40 countries. They have been instrumental in four cases that resulted in 15 arrests.

Thomas Peschak (Germany/South Africa) documents the relationship between endangered Amazon river dolphins, also known as botos or pink river dolphins, and the people with whom they share their watery home.

The Amazon river dolphin’s relationship with humans is complex. Traditional Amazonian beliefs hold that the dolphins can take on human form, and they are both revered and feared. Others see them as thieves who steal fish from nets and should be killed.

Thomas took these images in areas where local communities are creating opportunities for tourists to encounter the dolphins. This brings another set of problems: when they’re fed by humans, the dolphins become unhealthy and younger individuals don’t learn to hunt for themselves.

Sage Ono (USA) explores the abundant life around the giant kelp forests in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary.

Inspired by the stories told by his grandfather, a retired marine biologist, and by a photograph of a larval cusk eel, Sage acquired a compact underwater camera and decided to take up underwater photography.

After university, he moved to the coast near the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary to pursue his interest. Here, it’s the submerged world of the bay’s forests of giant kelp – the biggest of all seaweeds – and the diversity of life they contain, that have captured his imagination.

The winners of the Impact Award

On the occasion of the photo competition's 60th anniversary, the judging panel has awarded a special prize. The Impact Award is given to two of the 100 finalists to recognize a story that inspires hope and drives action for positive change.

Liwia Pawłowska (Poland) watches as a relaxed common whitethroat is gently held by a bird ringer.

Liwia is fascinated by bird ringing, and has been photographing ringing sessions since she was nine. She says that she hopes her photograph ‘helps others to get to know this topic better.’

Volunteers can assist trained staff at bird-ringing sessions, where a bird’s length, sex, condition and age are recorded. Data collected helps scientists to monitor populations and track migratory patterns, aiding conservation efforts.

Jannico Kelk (Australia) illuminates a ninu against the darkness of the outback.

Jannico spent each morning walking the sand dunes of a conservation reserve, searching for footprints that this rabbit-sized marsupial may have left the night before. Finding tracks near a burrow, he set up his camera trap.

The greater bilby has many Aboriginal names, including ninu. It was brought to near extinction through predation by introduced foxes and cats. Within fenced reserves where many predators have been eradicated, the bilby is thriving.

About the exhibition