Thoughts on conservation treatments of meteorites

By Zina Fihl

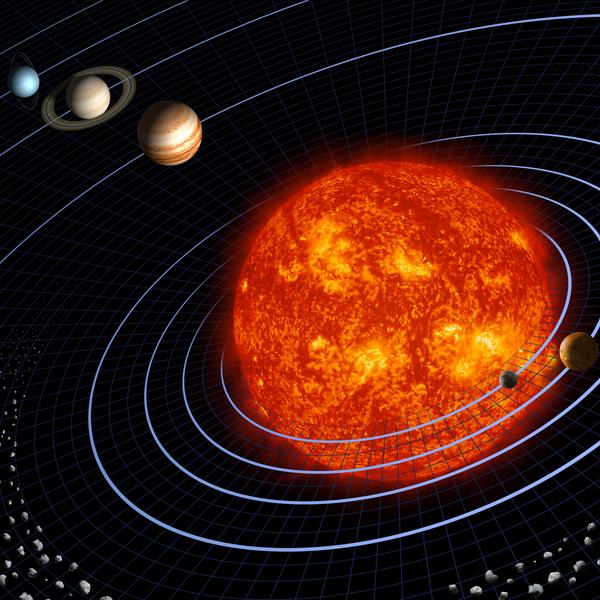

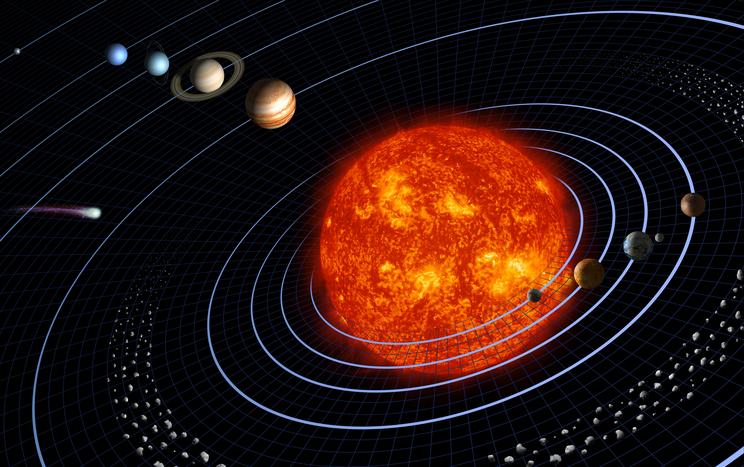

As you probably know, a meteorite is a rock that falls to Earth from space – that’s why these rocks are so cool! Most meteorites are pieces of asteroids, rocky bodies that orbit the Sun in the Asteroid Belt. Sitting between the planets Mars and Jupiter, the Asteroid Belt is between 478.7 to 628.3 million km from Earth! These rocks have travelled amazing distances. With current technology, it’s estimated to take more than 18 months to reach the Asteroid Belt from Earth, making it quite unlikely we will be visiting there anytime soon.

The diversity in meteorite composition reflects them being part of asteroid bodies. Like Earth, the composition is divided with core material like iron meteorites, mantle material like stony-iron meteorites and the crust material like stony meteorites. For scientists, different chemistry in the meteorites categorises them even further and define their origin in space.

To plan a conservation treatment for meteorites it is very important to not disturb the chemical composition, and like most conservation approaches, the less intervention, the better. As part of a scientific collection, researchers still need these specimens for new analysis, and it is important not to alter the composition of the meteorite with chemicals and solvents.

Seymchan

For scientists to analyze and retrieve information, they cut a piece from the meteorite and then prepare the sample before using advanced research techniques. The cut slice or piece can result in a beautiful sample itself, such as the Seymchan meteorite. The main part of meteorites doesn't need conservation as their preservation status is quite stable. For the Seymchan specimen, it is important that there is no oxidation of iron (corrosion) resulting in rust, and that the specimen is perfectly polished, as light might be shining through on exhibition. Beautiful, isn't it?

Chondrites

Stony meteorites, like chondrites, are also surprisingly stable. Even though the surface appears crumbly, it isn't falling off – but don't scratch it! An example of a chondrite is this Danish meteorite called Mern. Fun fact, meteorites are named after the closest city to the fall or find.

Millbillilie

This meteorite called Millbillilie is an achondrite from the asteroid called Vesta. This meteorite has a crack that had to be repaired to keep the two pieces together. Prior conservation a few years back was done to adhere the crack, using the reversible conservation approved adhesive, Paraloid B-72.

Savik 1

One specimen that needs more conservation work is this iron meteorite called Savik 1. It's part of the Cape York shower and was cut and prepared for research in 1925.

Today it has rusty spots along the edges which we want to remove for exhibition. Iron meteorites, compared to the stony meteorites, are much sturdier. Therefore, using specific chemicals will not change the chemical composition of the meteorite. We plan to “polish and etch” this specimen to make the iron pattern called Widmanstätten structure even more beautiful – but first we need to learn much more about it. Stay tuned for an update on the conservation treatment for this specimen!