Diorama diaries

By Anastasia van Gaver

Over the last few months, the conservation team completed the documentation, deinstallation, and specimen conservation treatment for five of these dioramas: three dioramas of tropical forests (with a rhinoceros, okapis, and orangutans) and two dioramas of Arctic landscapes (with walruses, and muskoxen).

Access and documentation

A diorama is a traditional way of displaying taxidermy, with lifelike animals set in a naturalistic habitat. These intricate displays were particularly popular in the late 19th and 20th centuries, when they started being used as a tool to give viewers a better understanding of what wild animals look like in their natural environments.

The deinstallation process started with the museum team carefully removing the large glass windows that shielded the dioramas. This allowed access for thorough documentation, first led by the digital team who 3D scanned each diorama, offering a unique perspective for conservation and potential online access.

Afterwards, the conservation team started their own documentation, taking detailed photographs, measuring dimensions of different elements (specimens, background materials, foreground materials), and checking the condition of each diorama. Using a condition report template created specifically for the dioramas to ensure efficiency and consistency, conservators spent several weeks making detailed notes of everything they observed.

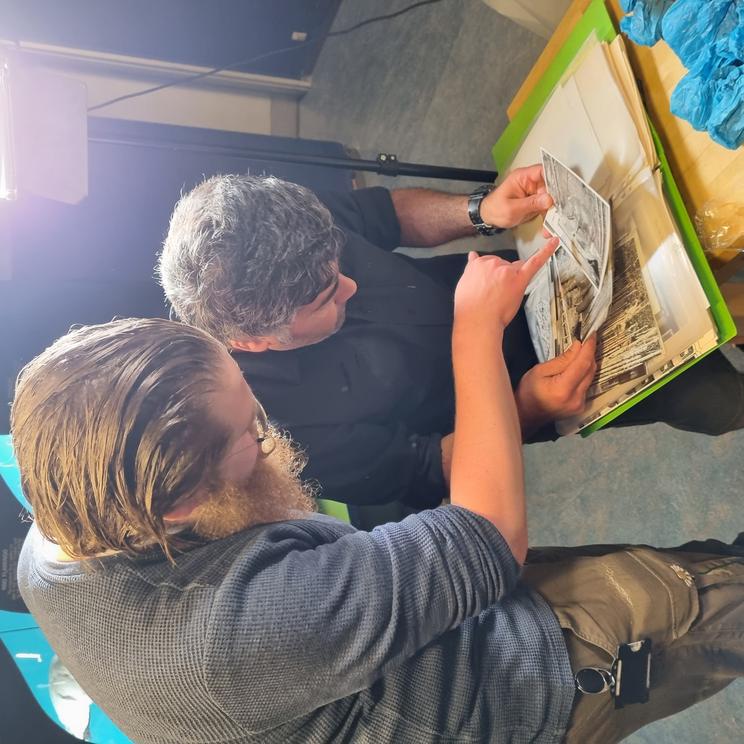

As part of the documentation process, they also consulted the museum archives to look at the makers’ notes, photographs, and models – some of the makers were even interviewed to explain their process. All those valuable insights really enriched the conservation process!

Deinstallation

Deinstalling specimens from the dioramas presented an array of challenges that required the conservation team to communicate effectively to ensure the safety of both specimens and team members. The confined space within the exhibition posed a logistical puzzle, and the sheer weight and size of some specimens, such as the rhinoceros, added an extra layer of complexity to the process.

During deinstallation, particular attention was given to fragile elements within the dioramas, such as the artificial plants mimicking the flora of the depicted ecosystems, that might get reused in future dioramas at the new museum building, or become part of the archival collection. To avoid breakage, elements that could be taken out of the dioramas were carefully removed, while others were simply protected in-situ.

Conservation treatments

While the specimens appeared to be in good condition inside their dim-lit dioramas, the conservators soon realised during the documentation process that the specimens would actually require interventive conservation treatments.

For example the diorama okapi mount selected for the new museum had large visible seam splits running along the length of the body and legs. Conservator Nicole Feldman used BEVA 371 and Japanese tissue paper fills, to stabilise the area and improve the aesthetics of the display specimen.

The orangutans, on the other hand, exhibited extensive fur loss revealing the skin and manikin material underneath. While treating that specimen, conservator Anastasia van Gaver covered the fur loss with a combination of fills and airbrushing.

Now that the specimens have been conserved, they will soon be heading to the new museum building. Once they are installed in the upcoming Biodiversity and Arctic galleries, we hope they will continue to inspire visitors for many years!

If you want to follow our work on dioramas, keep checking Conservators' Workshop for new posts. We will be writing about the conservation treatments of specimens, as well as the specific challenges of deinstalling the sixth diorama (with cranes in a Swedish raised bog).