A long-delayed jaguar

By Mikkel Ege Bartholdy

Most of the objects entering our conservation workshop on their way to the new museum require attention due to damage caused by long-term exhibition or storage.

However, others are prepared from new, and this jaguar (Pantera onca) is one such example.

This taxidermy specimen, distinguishes itself from other by being an almost fully prepared object, that never got to enter the exhibitions. The interesting story behind this jaguar mount was revealed through the work preparing the new museum galleries.

The jaguar, a 70kg male specimen, entered the museum collections in 1979. It was mounted in 1993, but the specimen was never fully completed. After pulling the hide over the mannequin, setting the glass eyes, finishing the facial expression, and pinning everything to place, the jaguar mount was put aside to dry and remained there for thirty years.

Now it has been selected to feature in our new rainforest exhibition and needed some minor work to finish it ready for display.

Active treatment of the jaguar

Condition

The jaguar preparation was incomplete with hundreds of now rusty nails holding the hide in place, and red iron-oxides covered the pins and the holes they were set in. In the period where the mount had been stored without a stand to keep it upright, claws were loosened and nails bent being pushed further into the body.

Other than this the condition proved fair, but as an unfinished object there was still plenty for conservation to do finish the jaguar. The full list of treatment required:

- Cleaning the fur of loose hairs, adhesive residue, and iron oxides.

- Removing the dried clay from the ears.

- Repairing and adhering the loose claws.

- Filling holes left by pins where they were the most apparent; placed where the fur was short, missing, or sparse.

- Painting and retouching the areas around eyes, the lips, and the snout.

- Adding in new whiskers, which had been lost in the thirty years of storage or while preparing the hide for mounting.

Treatment

The pins were removed by hand, and the accretions left behind were removed by gentle vacuum and brushing. The residue of hide-glue and matted parts of the fur was removed with a mixture of distilled water and ethanol (1:1 distilled water and 70% ethanol). The more steadfast clumps were sandwiched between wetted Wypall paper wipes and drawn out in direction of the hairs with slow motions.

The dried clay in the ears took nicely to reintroduced moisture with water. After a few hours of rewetting the clay could be removed in smaller fragments without pulling the hair out with them.

Claws were reset with Paraloid B-72 dissolved in acetone. The fur was pulled aside with tweezers, and the socket in the dry hide was painted with the dissolved resin before resetting the claw.

Since the jaguar never got further than setting of the hide, the exposed epidermis of the face had never been coloured. In nature this colouring often relies on active circulation in the live tissue, and the now desiccated areas require reintroduction of colour to appear alive and natural.

The pin-holes left behind around the eyes and nose were quite apparent, and prior to the painting these were filled with a paste mixed from Lascaux 498HV and glass micro Ballons tinted with dry pigments.

The first colours were painted on with Schmincke Aero Colour Professional through an airbrush. After this the painting was slightly corrected with hand-painting to work in some more uneven textures on the snout, and to help the transition area where the hairline met the bare skin around lips and eyes.

The last part of the treatment was to insert new whiskers. Not having the original whiskers in possession, we decided to use other hairs. Long white hairs from cape porcupine (Hystrix africaeaustralis) were perfect as they convincingly match the natural taper and curve of the jaguar whiskers.

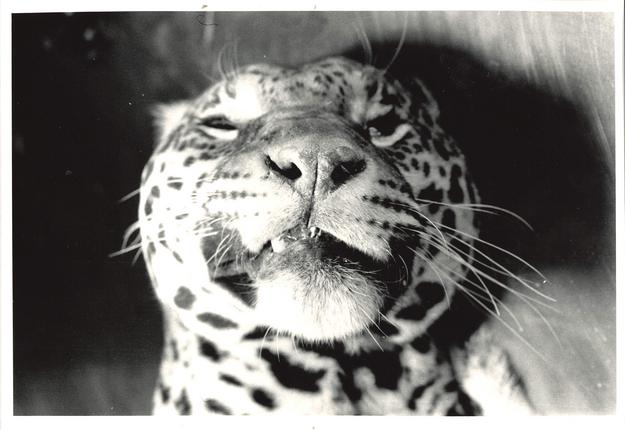

Entry holes were punched in the hide with a small awl, first over the eyes where the placement could mirror the right sides remaining whiskers. More loosely the remaining whiskers were placed on the sides of the muzzle, after consolidating the reference pictures taken more than forty years ago in 1979. The bases of the new whiskers were dipped into a bit of Lascaux 303HV before being placed into the ready-made holes.

The jaguar was slightly more presentable after being treated and is now in temporary storage. Waiting (not for too long this time!) to be installed at the new museum.

The original diorama model

While the jaguar was at the workshop an object appeared in the exhibition’s collections, alluding to the original plan for this taxidermy piece.

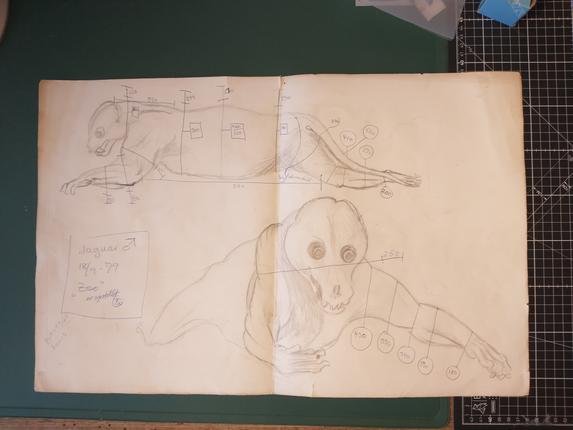

This object was a small-scale model in scale 1:10 built by conservator Bo Bindel. This was an early preparation for a rainforest diorama depicting South-American wildlife, as a part of the “From pole to pole” permanent exhibit at the Zoological Museum!

Even though the jaguar was almost completed in 1993, this diorama was never built. Connoisseurs of the exhibits at the Zoological Museum can recall the “Christmas-diorama” unveiled every December in the latest years. This is the space that the jaguar-diorama was originally planned to fill.

This scale model is a physical concept of the diorama in its roughest rendition, and most of the existing dioramas in the exhibitions here have been made with physical scale models as a guide and tool in the imagining of the builds. Habitat dioramas are incredibly involved exhibition types requiring a deep understanding of lighting and spatial awareness, to uphold the illusion of an actual scene from nature. A physical model is quick to produce and change, requiring no digital rendering of light and models, and is an easy way to show “proof of concept”.

The scale model was accompanied by several photographs and notes about the proposed build. In addition to this, there was a short list of proposed species that potentially could be a part of the diorama: Jaguar, piranhas, king vulture, iguana, boa, electric eel, and chameleon. Our interest was piqued and the hunt was on to find more information about this non-existing diorama!

It coincided that collections manager Anders Illum was looking for objects for the new exhibitions, while during his search, he ran into several objects marked “for jaguar-dio” among the collection of casts and experiments made by previous conservators at the museum.

Among these objects were several reptiles to inhabit the diorama, photo studies of piranhas, and notes about preparation and molding of realistic fish specimens. All of this together with the list of species from earlier can give us an idea of how the diorama would take form, and hint towards the extreme species richness in South American rainforests.

Among other artefacts found in this hoard were several photographs and observations about backlighting-effects for the diorama, and several cutouts of nature-magazines. The latter collected as reference for Bo’s taxidermy work on the jaguar. He mounted the jaguar lying along the length of a large root or tree-trunk, and the scale-model gave insight into the “levitating” full-mount that entered the workshop.

Lastly a single paint-stand (top right of previous picture) was found with the same note linking it to the diorama, however the fish model at used to be here has been removed, presumably used somewhere else in the vast exhibitions and outreach projects at the Zoological Museum, fulfilling its raison d’etre before the other casts in this group.

Finally all of these documents, notes, references, casts and preparations for a planned but not executed exhibition piece suggest just how comprehensive a job it can be to teach and mediate knowledge and passion for nature as a museum. Remember this is just one man, Bo’s, work prior to the collaboration with other professionals from the museum’s collections, outreach, craftsmen, researchers, etc. to refine and execute it.

Thus, a random look on the bottom shelf of the exhibition collection turned into a short story from the museum’s time at Universitetsparken. The jaguar and many of the other objects are now, after 30 years with “jaguar dio” labels on shelves in storage, ready to fulfill their intended purpose. They will be a part of the dissemination at the Natural History Museum of Denmark when our new museum opens.